CardioBrief: “A Case of Plagiarism Raises Blood Pressures”

As discussed by Larry Husten on CardioBrief, a 2011 review article in Korean Circulation Journal appears to plagiarize from a 2009 article that was published in Journal of the American College of Cardiology. I spent several hours comparing the two articles, and found that several paragraphs in the KCJ article consisted primarily of paraphrasing, without attribution, of text from the JACC article. In addition, the majority of references in the KCJ article and two of the figures are the same as in the JACC article, and several of the headings are the same or very similar. The KCJ article does not cite the JACC article at all.

The JACC article is by Franz Messerli and Gurusher Panjrath. The KCJ article is by Chang Gyu Park and Ju Young Lee.

Moreover, Figure 4 in the KCJ article appears to have been copied from figure 1 in the 2009 revised European Guidelines on Hypertension Management, although the figure instead references a 2006 study by Messerli and colleagues that was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

See Larry’s post on CardioBrief for more details.

Update: Larry reports that the editor of KCJ contacted him to say that the article is now being investigated by the publishing committee of the Korean Society of Cardiology and that an additional investigation has been requested from the Ethics Commission of the Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors.

Comment period on “Sunshine” regulations closes

Section 6002 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires disclosure of payments by the drug and device industry to physicians and teaching hospitals. On December 14, 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services proposed regulations that would implement these “sunshine” provisions. See this Pharmalot post for background. I also recommend this commentary by Robert Steinbrook and Joseph Ross. The comment period closed on February 17, and I submitted a comment, excerpted below. You can access the proposed regulations and comments by going to www.regulations.gov and searching on “CMS-5060-P.”

Re: Transparency Reports and Reporting of Physician Ownership or Investment Interests; CMS-5060-P

Dear Ms. Tavenner:

I am writing to support the adoption of the above-referenced proposed rules implementing section 6002 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA). As you know, this section of the PPACA requires drug, device, biological, or medical supply manufacturers to report certain payments and transfers of value to covered recipients, entities, individuals and teaching hospitals. The reported information would be available on a public website.

I believe the rules should be adopted substantially as proposed. In particular, I believe it is essential for the rules to require disclosure of both direct and indirect payments. Indirect payments include those a company makes to a third party, such as a medical society, contract research organization, or medical education and communication company, but that are ultimately intended for a physician or other covered recipient. The reporting of indirect payments is essential to meet the goals of transparency and completeness and to prevent the institution or continuation of arrangements that impede full disclosure of the financial relationships between industry and the medical profession.

In addition, I urge you to give careful consideration to the design of the proposed website. It should be designed to make possible it easy for members of the general public to find all payments to a particular provider or entity in one search regardless multiple addresses or variations in names (e.g., with or without a middle initial). I urge CMS to provide an opportunity for public discussion and comment on the proposed website design, such as through a public forum and/or focus groups.

Finally, I urge CMS to provide greater detail on specific enforcement mechanisms to ensure that manufacturers comply promptly and completely with the reporting requirements.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this important proposed regulation.

Sincerely,

Marilyn Mann

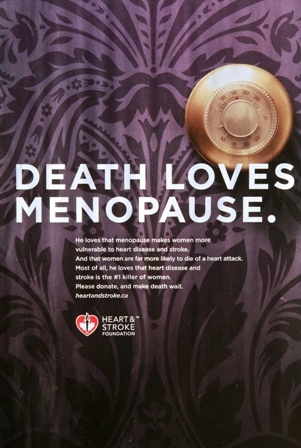

Heart and Stroke Foundation “make death wait” campaign: effective advocacy or unnecessary scare tactics?

I would be interested to know what my readers think of the two Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSF) ads shown below. The ads are part of HSF’s “Make death wait” awareness and fundraising campaign that’s been going on for the last few months. In the first ad, shown in this You Tube video, several different women are shown as a male voice, meant to personify death, intones “I love women. I love older women, professional women, stay-at-home moms. I love how women put their family first. I love how you’re so concerned that I’ll get to your husband.” In the last scene a woman in a bathing suit looks apprehensively over her shoulder as the voice warns, “You have no idea that I’m coming after you.” Eileen Melnick McCarthy, director of communications for the foundation, told a reporter that the intent of the campaign is to “wake up Canadians to the threat of heart disease and stroke.”

In addition, the print ad that appears below has appeared in a Canadian magazine. The copy, in case you can’t make it out, reads as follows:

Death loves menopause. He loves that menopause makes women more vulnerable to heart disease and stroke. And that women are far more likely to die of a heart attack. Most of all, he loves that heart disease and stroke is the #1 killer of women. Please donate, and make death wait.

Is this a legitimate way to “wake up” people to the threat of cardiovascular disease? Or unnecessary and counterproductive scare tactics? I lean toward the latter.

Hayward and Krumholz: Open Letter to the Adult Treatment Panel IV of the National Institutes of Health

Rodney Hayward and Harlan Krumholz have published an open letter to the committee that is currently engaged in writing updated guidelines for cardiovascular risk reduction. Their letter challenges the committee to replace the current “treat to target” paradigm with a “tailored treatment” approach, as discussed below.

The primary focus of the current set of guidelines, ATP III , was a strategy of treating patients to target LDL-cholesterol levels, known as the “treat to target” paradigm. Moreover, the “cutpoints,” or triggers, for initiating therapy are also based on LDL levels, with higher risk patients having lower cutpoints. However, as Hayward, Krumholz and colleagues have previously argued (see here, here and here), the treat to target paradigm was not based on the results of clinical trials, since no major randomized controlled trial has tested the benefits of treating patients to LDL targets. Rather, the trials have used fixed doses of lipid-lowering drugs.

Hayward and Krumholz argue that LDL levels are not particularly useful in assessing the 2 factors that help determine the benefit of a treatment for an individual patient: (1) risk of morbidity and mortality in the absence of treatment (baseline risk) and (2) the degree to which the treatment reduces that risk. For calculating baseline risk, LDL is only one of several factors that are considered, including age, gender, smoking, blood pressure, HDL, and family history of premature cardiovascular disease and in most cases contributes little to the estimate of cardiovascular risk. For the second factor, clinical trials of statins demonstrate that the relative benefits of statins are not substantially related to pretreatment LDL levels. Thus, a high risk person may have low LDL levels and a low risk person may have high LDL levels and the high risk person will derive more absolute benefit more from treatment even though his or her LDL is low (illustrated in this table).

Hayward and Krumholz also argue that treating to LDL targets can lead to treatments that have not been shown to be safe. The treat to target approach can mean initiating treatment in patients at a relatively young age, leading to potentially many years of statin treatment. The long-term safety of this approach is not yet known. In addition, the perceived need to reach an LDL target often leads to the addition of nonstatin drugs such as niacin and ezetimibe when the maximum dose of a statin is reached and the patient’s LDL is still above goal. The benefit and safety of adding these drugs on top of statin therapy has not yet been demonstrated.

The “tailored treatment” approach Hayward and Krumholz advocate bases intensity of statin treatment on a person’s 5- or 10-year cardiovascular risk. In a previous paper, Hayward et al. tested a tailored treatment model of primary prevention using 5-year coronary artery disease (CAD) risk and compared it with the treat to target approach. In their model, a person with 5% to 15% risk would be prescribed 40 mg simvastatin and a person with greater than 15% risk would be prescribed 40 mg atorvastatin. Using this simulated model, the tailored treatment approach was found to prevent more CAD events while treating fewer persons with high-dose statins as compared to the treat to target approach.

For the reasons stated above, the tailored treatment approach does appear to me to be superior to the treat to target approach. At the same time, I note that the decision to take a statin is a personal decision. For primary prevention, the absolute benefit for most people of taking a statin over a 5 or 10 year period is small. Each person should calculate their baseline risk (there are online risk calculators for this), look at how much their risk can be lowered with a statin, and ask themselves if the benefit seems worth it to them in terms of cost, inconvenience and possible side effects (including a small increase in risk of developing diabetes).

In addition, I note that neither approach is designed to apply to patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Due to the very high risk of premature coronary heart disease in FH patients (approximately 85% of male FH patients and 50% of female FH patients will suffer a coronary event by age 65 if untreated), the treatment paradigm for FH patients is that all are treated with statins starting in childhood or early adulthood (not everyone agrees that it is necessary to start treatment in childhood but that’s a topic for another day). In other words, FH patients are treated based on their lifetime risk, not their 5- or 10-year risk.

References

Hayward RA, Krumholz HM. Three reasons to abandon low-density lipoprotein targets: an open letter to the Adult Treatment Panel IV of the National Institutes of Health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012:5;2-5.

Hayward RA, Hofer TP, Vijan S. Narrative review: lack of evidence for recommended low-density lipoprotein treatment targets: a solvable problem. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:520-530.

Krumholz HM, Hayward RA. Shifting views on lipid lowering therapy. BMJ. 2010;341:c3531.

Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Zulman DM, Timbie JW, Vijan S. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:69-77.

Rind DM. Intensity of lipid lowering therapy in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. In: Freeman MW, Sokol HN, eds. UpToDate. 19.3 ed.

Abbott Laboratories sponsors review article on its own drug

A review article in a medical journal is an attempt to summarize the current state of research on a particular topic. A review article does not present original research but rather collects and interprets the research that has been done, describes gaps in the research and controversies that exist, and how to apply the research in clinical practice. A review article can be a good starting point to get a grasp of a topic. However, because the authors are generally experts on the topic they are discussing, they often have a point of view that may not be obvious to someone not expert in the field.

But what if the agenda for the article were out in the open? What if, say, a drug company sponsored a review article on its own drug and paid a medical journal to publish it? That appears to have happened with this review article on fibrates in a journal called Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, published by MedReviews, LLC. The acknowledgment discloses the following:

Abbott Laboratories, Inc., provided funding to MedReviews, LLC. No funding was provided to authors. Abbott Laboratories, Inc. had the opportunity to review and comment on the publication content; however, all decisions regarding content were made by the authors.

So, while it is unclear who produced the initial draft of the article, Abbott Laboratories reviewed and commented on the article before publication and paid the publisher for publishing the article. Abbott just happens to sell two fibrates, TriCor and Trilipix.

Never having heard of this journal, I looked at the journal’s website and confirmed that it is a peer-reviewed journal and is indexed in PubMed and Medline. It’s editorial board includes some well-known academic physicians. The website also discloses that MedReviews has formed a partnership with the California Chapter of the American College of Cardiology.

I’m having a hard time understanding why anyone would want to spend their time reading a medical journal that publishes review articles that have such a high level of involvement from a commercial enterprise with a vested interest in the topic. I’m also having a hard time understanding why the California Chapter of the ACC and the members of the editorial board would want to be associated with this journal.

H/T Harlan Krumholz.

Addendum January 7, 2012: Howard Brody has weighed in on the Hooked: Ethics, Medicine, and Pharma blog.

Addendum January 10, 2012: Also see this post on Pharmalot blog.

Addendum February 3, 2012: Also see this post by Kevin Lomangino on the Health News Watchdog blog and this followup post by Howard Brody.

Addendum August 16, 2012: See this followup post by Kevin Lomangino on the Health News Watchdog blog.

“Choosing Wisely” campaign launched

The ABIM Foundation has joined with nine medical specialty societies to develop evidence-based lists of tests and procedures for patients and physicians to discuss and question. The goal of Choosing Wisely is to help physicians, patients and other stakeholders avoid unnecessary and in some cases harmful interventions and reduce the ever-expanding cost of health care. Each participating specialty society will identify five tests or procedures whose use should be questioned. The lists will be announced in April 2012. The lists are modeled after the National Physicians Alliance project “Five Things You Can Do in Your Practice,” which was funded by the ABIM Foundation. Consumer Reports will also be participating in the campaign. One page factsheet here. Press Release here. Website here.

Plant sterol controversy discussed in JAMA

Oliver Weingartner and colleagues have a letter in the current issue of JAMA, responding to the publication of a trial of the “portfolio diet” of cholesterol-lowering foods, including margarine fortified with plant sterols.

To the Editor: In their study on dietary strategies to reduce serum cholesterol levels, Dr Jenkins and colleagues concluded that a dietary portfolio including plant sterols resulted in greater reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels during a 6-month follow-up compared with low-saturated-fat dietary advice. Although a significant LDL-C lowering achieved by a dietary portfolio including plant sterols may be beneficial, we believe the results do not necessarily support a heart health benefit. In Table 3 of the article, the plant sterol–fortified dietary portfolio reduced serum cholesterol levels at the expense of an increase of plasma plant sterol levels (10.7 μmol/L at baseline and 13.3 μmol/L at week 24). (To convert phytosterols to mg/dL, multiply by 0.04.)

Our research group has previously assessed the effect of lipid lowering with ezetimibe or phytosterols in apolipoprotein E (apoE) −/− mice. We found that plasma plant sterol concentrations were strongly correlated with increased atherosclerotic lesion formation (r = 0.50), suggesting that plant sterols may be atherogenic. Based on a rare inherited disease called phytosterolemia, characterized by overabsorption of phytosterols and premature coronary artery disease, and several epidemiological studies that have shown a correlation between increased plant sterol plasma levels and cardiovascular risk, the role of plant sterols in the management of hypercholesterolemia has become controversial. Studies assessing hard cardiovascular end points are needed before conclusions that a diet enriched with plant sterols reduces cardiovascular risk can be drawn. (citations omitted)

The essential point, as made by many people in recent years (see, e.g., this commentary), is that it is not enough to show that an intervention lowers LDL (or raises HDL, etc.). Before we can be sure that the intervention is beneficial, we need evidence that it lowers the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

In their reply, Vanu Ramprasath and colleagues note that some epidemiological and animal studies have not found risk associated with increased plant sterol levels and the fact that statins may increase absorption of plant sterols. In summary, they state that “based on evidence from both humans and animal models, we believe that plant sterol levels in plasma are not related to increased CHD risk.”

A comment about this summary statement. There really is no controversy about whether high levels of plant sterols cause heart disease: because of the association of premature heart disease with the rare genetic disease sitosterolemia, everyone agrees that they do. The issue is whether more moderate increases in plant sterol levels are harmful.

So the controversy continues.

Sunday links

David Rind recently revived his blog Evidence in Medicine and has a post up on the SHARP trial. The SHARP trial, which I discussed recently on this blog and on Gooznews, is the basis for Merck’s application for a new indication for its drugs Vytorin (ezetimibe/simvastatin) and Zetia (ezetimibe). David explains why the results in SHARP are consistent with previous evidence on the effect of statins in patients with chronic kidney disease, both pre-dialysis and on dialysis.

Kevin Lomangino has an article up on the “portfolio diet,” which is a diet that emphasizes foods that lower cholesterol. Kevin explains that most of the cholesterol-lowering from this diet comes from the inclusion of foods containing added plant sterols. As I previously discussed on this blog, while plant sterols lower LDL, their effect on cardiovascular events is unknown, making the portfolio diet a bit of a crapshoot healthwise.

10 steps to better risk communication

Every day, patients are faced with difficult medical decisions. These decisions invariably involve tradeoffs between risks and benefits. However, these risks and benefits are often not communicated in a way the patient can understand, if they are communicated at all. In a commentary in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Angela Fagerlin and colleagues highlight 10 methods that have been shown to improve understanding of risk and benefit information. Their commentary uses examples relating to cancer screening, prevention, and treatment, but the principles should apply in other areas. Below I summarize the key points; the authors state that the first three recommendations are based on strong evidence, while the rest are based on preliminary evidence.

- Communicate using “plain language.” According to the authors, the average American reads at an 8th grade level, but health education materials are often written at a high school or college level, making the information hard for the average person to understand.

- Present statistical information using absolute risk rather than using relative risk or number needed to treat formats. Changes in risk appear larger when presented using relative risk rather than absolute risk. Absolute risk is easier for most people to understand than number needed to treat.

- Use pictographs when possible when presenting information graphical format. The authors state that pictographs are easier to understand than other types of graphs, such as bar graphs and pie charts.

- Present data using frequencies rather than percentages. “10% of patients get a bad rash” and “10 out of a hundred patients get a bad rash” mean the same thing, but percentages are more abstract and/or harder to understand for some people.

- When discussing treatment complications or side effects, differentiate between baseline risks and incremental risks. Baseline risks are risks the person would face without any treatment; incremental risks are the risks associated with treatment. For example, an initial pictograph could show baseline risk and a second pictograph could add a new color to represent the additional people who would experience the side effect as a result of the treatment.

- Be aware that the order of presenting risks and benefits can alter risk perceptions. For example, if the benefits are presented first and the risks second, the risks may be perceived to be more worrisome and common. This issue can’t be avoided altogether, but can be minimized by summarizing all the information at the end.

- When there are numerous risks and benefits, use a summary table. Many treatments have numerous risks and benefits. It is easier to compare the risks and benefits if they are presented in a summary table.

- Recognize that comparative risk information can bias decision making by altering how a person views his or her own risk. If a person is given information indicating that their risk of developing a disease is higher than average, they may be more likely decide in favor of an intervention. Decisions should be based on whether the benefits of the intervention outweigh its risks for an individual person, which can only be decided based on absolute risk.

- Consider that providing less information may be more effective. Presenting more information can distract people from focusing on the key pieces of information that are needed for decision making.

- Make clear the time interval over which a risk occurs (e.g., 5-year risk, 10-year risk, 20-year risk).

I recommend reading the entire commentary. If you don’t have access to the PDF, email me and I will send it to you.

Why the new indication for Vytorin and Zetia should not be approved

I have a guest post up at Merrill Goozner’s blog explaining why Merck’s application for a new indication for its drugs Vytorin (simvastatin/ezetimibe) and Zetia (ezetimibe) should not be approved. The proposed indication is for the reduction of major cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease and is based on the results of the SHARP trial. However, because SHARP compared the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe with placebo — there was no simvastatin arm — we have no way of knowing if ezetimibe contributed anything to the result. The FDA requires that combination drugs have additive effects over either drug alone. Merck has not shown that ezetimibe contributed anything to the effect in SHARP, so the new indication should not be approved.

Addendum January 25, 2012: Merck issued a press release today stating that the FDA did not approve the new indication. “Because SHARP studied the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe compared with placebo, it was not designed to assess the independent contributions of each drug to the observed effect; for this reason, the FDA did not approve a new indication for VYTORIN or for ZETIA® (ezetimibe) and the study’s efficacy results have not been incorporated into the label for ZETIA.” The SHARP results were incorporated into the Vytorin label (see pages 27-28).

Addendum, May 5, 2015: Unfortunately, the GoozNews blog is no longer up on the web.